We were thrilled to visit and teach new friends from the first responder community in and around Lock Haven, PA this past week. We listened to our audience’s experiences and training goals, learned how tremendously professional and caring they are in their work, then launched into delivering “Disability is Not a Crime” content.

Everyone in the room had autism or an autistic relative, and one learner manages two autistic employees, so engagement was high. The conversation was so fantastic we stayed well past the end time of 9:00pm, thinking of creative ways to support autistic people in emergency situations.

Blending an autistic presenter (who is an EMT) and a non-autistic trainer seems to help people feel comfortable asking questions no matter their personal experience. We left feeling a little sad that we don’t live closer to experience their beautiful area and work together more to support folks with disabilities in the region.

Huge thanks to Goodwill Hose Company Ambulance Association for hosting us! And thank you to the attendees for sharing stories of finding missing persons who wander (some multiple times), supporting autistic people in car accident responses, and for telling us a few rattlesnake stories we don’t often get to hear!

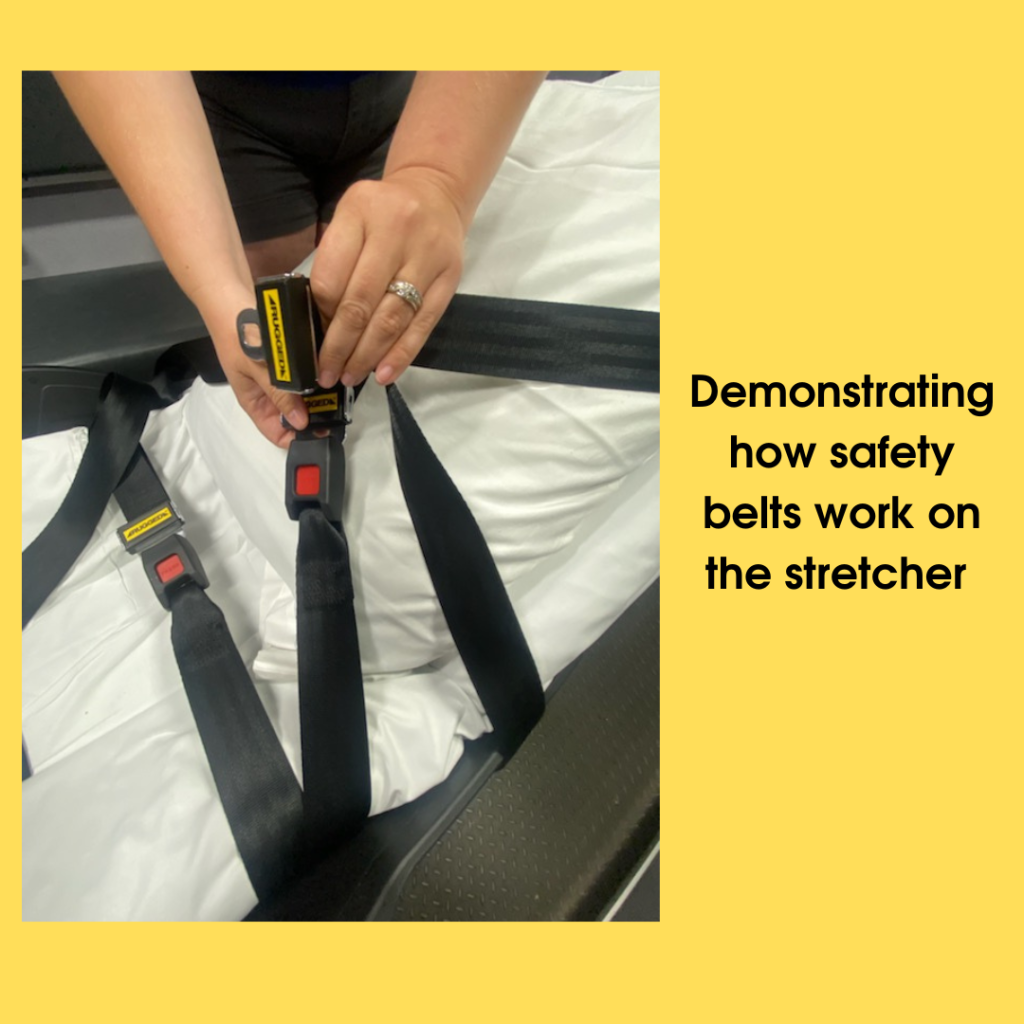

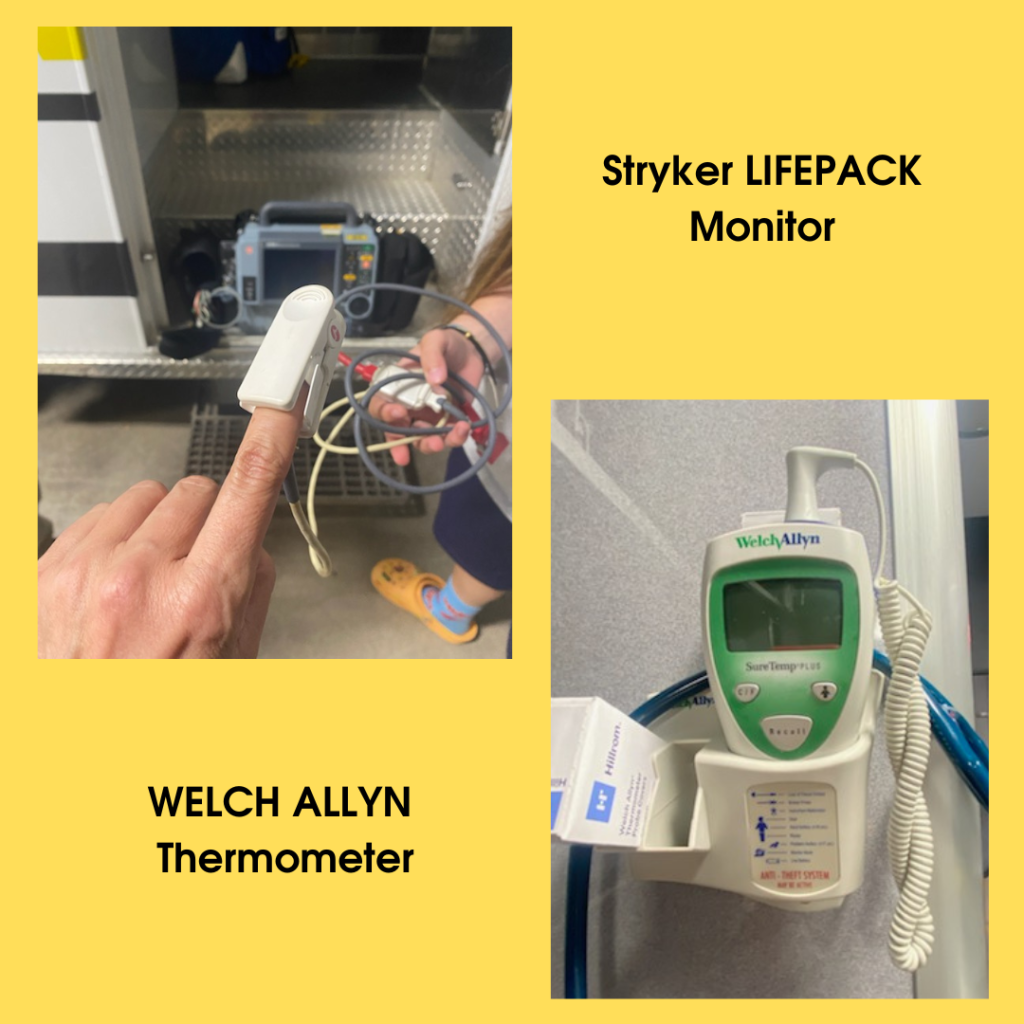

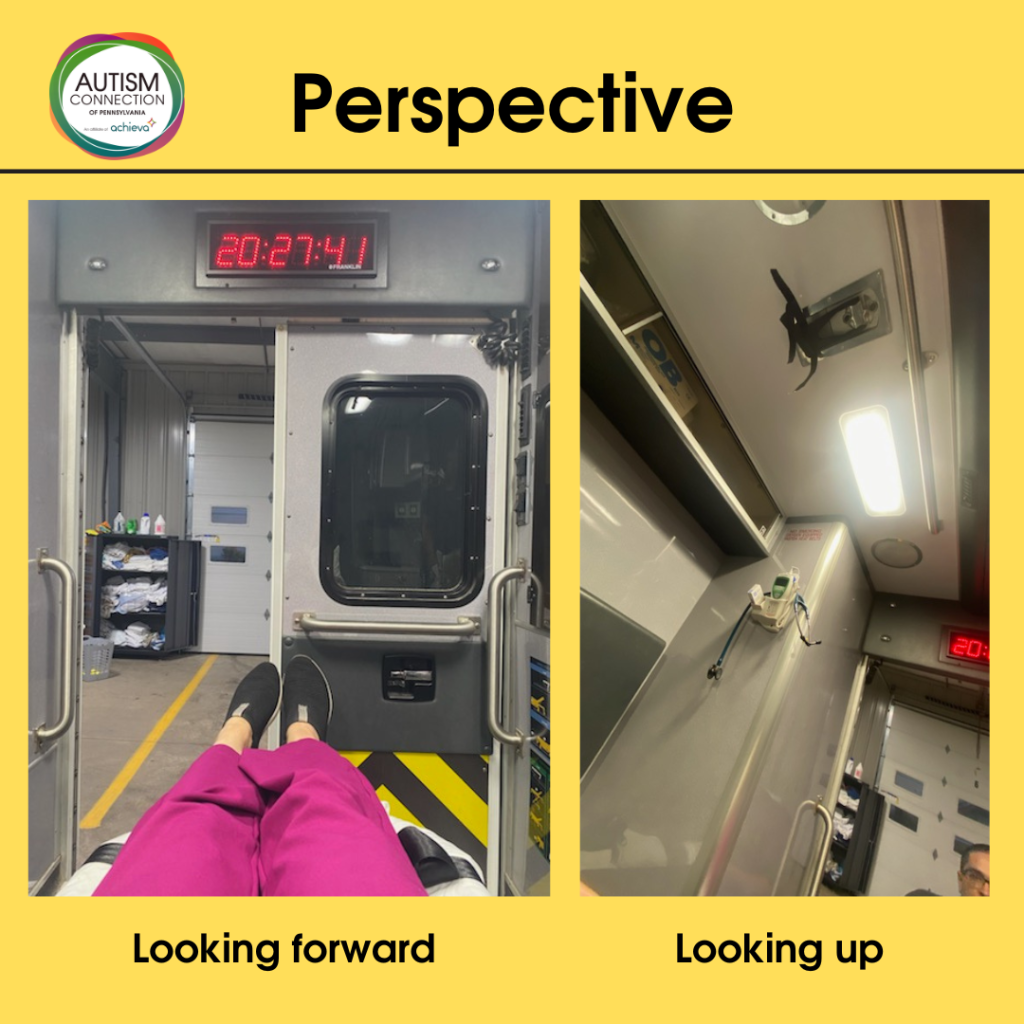

Since we were at an EMS base for the training, we had the opportunity to take some photos of equipment. We will be using the images to help people understand what to expect in emergency situations in an ambulance. People may be safer if they know a little more about what to expect when they are sick or injured. Believe it or not, it is not uncommon for people to be arrested and charged for fear-based behaviors they may have during emergency situations, when they are injured or sick on the scene, or in an emergency room.

This project is funded by the Pennsylvania Developmental Disabilities Council.